Incremental Progress

Before my MS attack, I was a huge high-achiever. Everything I did (in my career) was focused on higher quantity and higher quality outputs. As soon as that norm was taken away, due to MS, I started to shift my approach to goals to be less about impressive numbers. I stopped thinking so much in terms of outputs and more about outcomes.

Honestly, this mental shift came from the despair at a future that no longer seemed to be bright—I could lose all of my abilities again, at any time, for any reason. Despite being born from a place of anger and depression, there may be a hopeful side of this way of thinking.

But first, here’s the system I’m talking about and how I follow it (generally speaking).

Goals are now visions. No more outputs, let’s consider the outcomes. An “output” is some kind of product. Something tangible, something that is measurable. It’s basically what you’ve always been told a “goal” is.

Here’s the thing, though. In Soccer (Football), a goal is just a container. The ball doesn’t have to enter it through one, specific, precise way. It just has to get past the Goalie and into the net. Why do we, then, call our outputs goals? The output in the Soccer analogy isn’t winning, it’s the effort put into moving the ball up the field and into the goal. If I set a “goal” to dribble the ball 5 times, that does not inherently add a score to my team’s scoreboard. It might be the reason I got the ball into the right position to score, but if I only focus on how many times I dribble, I may never end up shooting.

The real goal shouldn’t be the thing that is measured. It should just be the vision of where I want to go, and it should be something that is outcome determinative. The outcome I want as a Soccer player is to win the game, not to be seen dribbling 5 times. Our outputs should be getting us closer to the outcome we want.

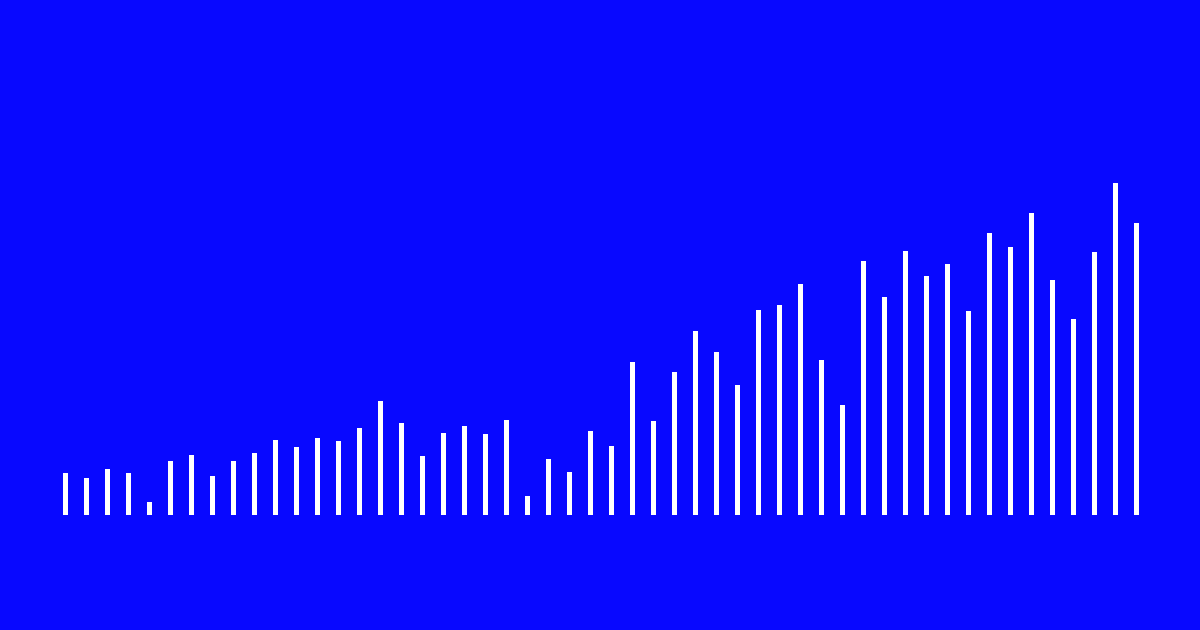

Systems are now our measurement and our motivation. I have long been fascinated with the compound effect: Small, incremental progress that builds on itself and becomes powerful and momentous after significant time and effort.

As I learned in Behavioral Psychology, rats will always take the smaller, sooner reward over the larger, later one. We, like rats, are heavily tempted by the prospect of quick wins that are right in front of our noses, but with some vision and self-determination, we are able to see past the immediate gain and choose the larger, later reward. The compound effect requires that same vision and self-determination. It’s a system that is discouraging and easy to quit on if you don’t have that vision. If you do catch the vision, though, the pay-off is monstrously larger than you could have expected from an easier path.

The reason this is more interesting to me now—even with my understanding that I can’t bet on my future anymore—is that it requires daily, consistent effort. The daily stuff is all I have. I can’t rely on anything that causes me to put off something for the future, because I only have today.

Systems have become my way of making progress, because it activates me right now. If I can do something today that contributes to my ultimate outcome, I can do it, and trust in the system that it is working out the payoff for me.